John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

,

psychologist, and

educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the first half of the twentieth century.

The overriding theme of Dewey's works was his profound belief in

democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

, be it in politics, education, or communication and journalism. As Dewey himself stated in 1888, while still at the

University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

, "Democracy and the one, ultimate,

ethical ideal of humanity are to my mind synonymous." Dewey considered two fundamental elements—schools and

civil society

Civil society can be understood as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business, and including the family and the private sphere.[public opinion

Public opinion is the collective opinion on a specific topic or voting intention relevant to a society. It is the people's views on matters affecting them.

Etymology

The term "public opinion" was derived from the French ', which was first use ...]

, accomplished by communication among citizens, experts and politicians, with the latter being accountable for the policies they adopt.

Dewey was one of the primary figures associated with the philosophy of

pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that considers words and thought as tools and instruments for prediction, problem solving, and action, and rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. ...

and is considered one of the fathers of

functional psychology

Functional psychology or functionalism refers to a psychological school of thought that was a direct outgrowth of Darwinian thinking which focuses attention on the utility and purpose of behavior that has been modified over years of human existen ...

. His paper "The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology," published in 1896, is regarded as the first major work in the (Chicago) functionalist school of psychology. A ''

Review of General Psychology

''Review of General Psychology'' is the quarterly scientific journal of the American Psychological Association Division 1: The Society for General Psychology. The journal publishes cross-disciplinary psychological articles that are conceptual, the ...

'' survey, published in 2002, ranked Dewey as the 93rd-most-cited psychologist of the 20th century.

Dewey was also a major educational reformer for the 20th century.

A well-known

public intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or ...

, he was a major voice of

progressive education

Progressive education, or protractivism, is a pedagogical movement that began in the late 19th century and has persisted in various forms to the present. In Europe, progressive education took the form of the New Education Movement. The term ''pro ...

and

liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

. While a professor at the

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

, he founded the

University of Chicago Laboratory Schools

The University of Chicago Laboratory Schools (also known as Lab or Lab Schools and abbreviated as UCLS though the high school is nicknamed U-High) is a private, co-educational day Pre-K and K-12 school in Chicago, Illinois. It is affiliated with ...

, where he was able to apply and test his progressive ideas on pedagogical method. Although Dewey is known best for his publications about education, he also wrote about many other topics, including

epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epis ...

,

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

,

aesthetics

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed t ...

,

art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

,

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

,

social theory

Social theories are analytical frameworks, or paradigms, that are used to study and interpret social phenomena.Seidman, S., 2016. Contested knowledge: Social theory today. John Wiley & Sons. A tool used by social scientists, social theories rel ...

, and

ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concer ...

.

Early life and education

John Dewey was born in

Burlington, Vermont, to a family of modest means. He was one of four boys born to Archibald Sprague Dewey and Lucina Artemisia Rich Dewey. Their second son was also named John, but he died in an accident on January 17, 1859. The second John Dewey was born October 20, 1859, forty weeks after the death of his older brother. Like his older, surviving brother,

Davis Rich Dewey

Davis Rich Dewey (April 7, 1858December 13, 1942) was an American economist and statistician.

He was born at Burlington, Vermont. Like his well-known younger brother, John Dewey, he was educated at the University of Vermont and Johns Hopkins Unive ...

, he attended the

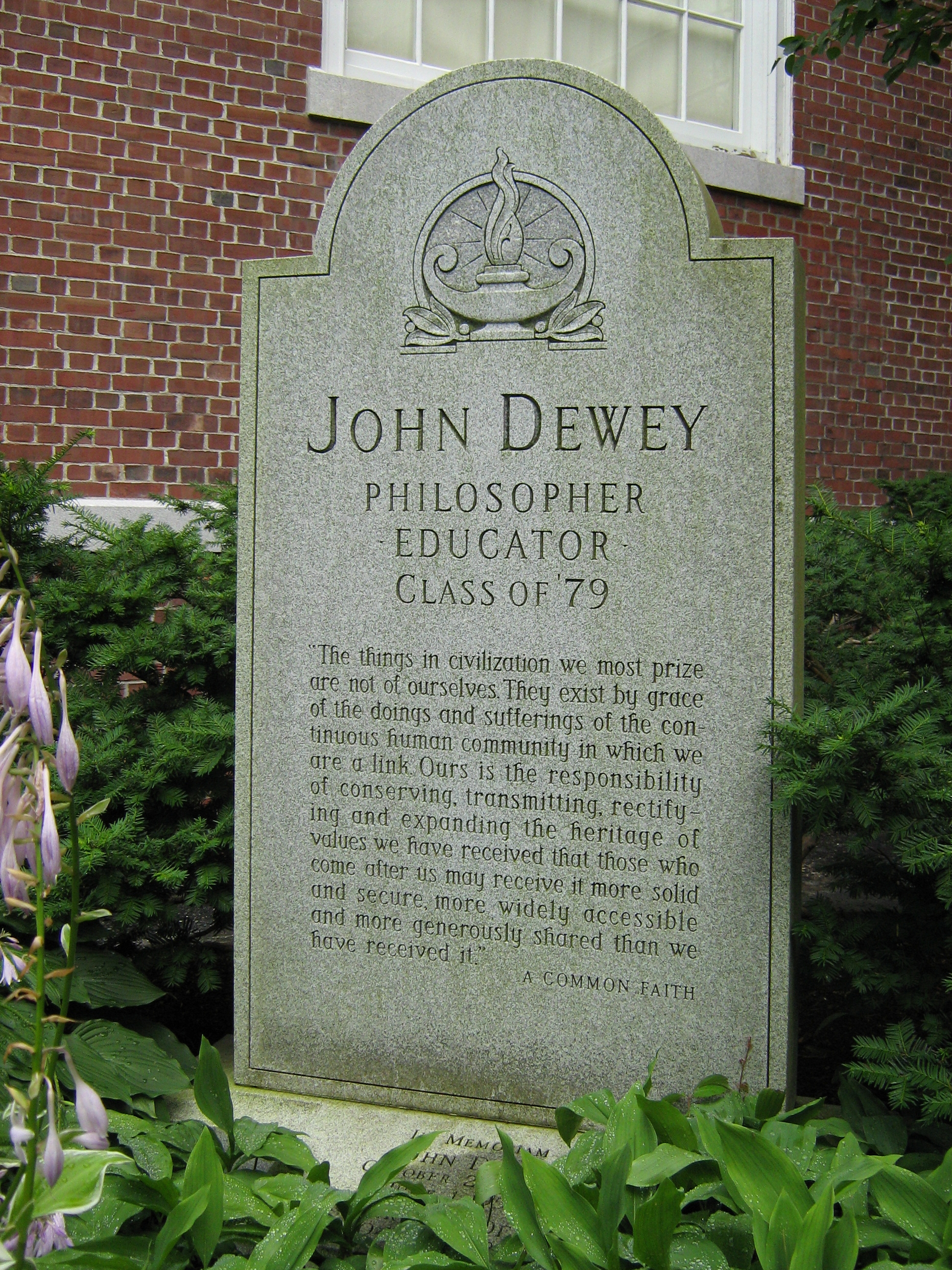

University of Vermont

The University of Vermont (UVM), officially the University of Vermont and State Agricultural College, is a public land-grant research university in Burlington, Vermont. It was founded in 1791 and is among the oldest universities in the United ...

, where he was initiated into

Delta Psi

St. Anthony Hall or the Fraternity of Delta Psi is an American fraternity and literary society. Its first chapter was founded at Columbia University on , the feast day of Saint Anthony the Great. The fraternity is a non–religious, nonsectaria ...

, and graduated

Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

in 1879.

A significant professor of Dewey's at the University of Vermont was

Henry Augustus Pearson Torrey (H. A. P. Torrey), the son-in-law and nephew of former University of Vermont president

Joseph Torrey. Dewey studied privately with Torrey between his graduation from Vermont and his enrollment at

Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hem ...

.

Career

After two years as a high-school teacher in

Oil City, Pennsylvania, and one year as an elementary school teacher in the small town of

Charlotte, Vermont

Charlotte is a New England town, town in Chittenden County, Vermont, Chittenden County, Vermont, United States. The town was named for Queen Charlotte, though unlike Charlotte, North Carolina, Charlottesville, Virginia, and other cities and towns ...

, Dewey decided that he was unsuited for teaching primary or secondary school. After studying with

George Sylvester Morris,

Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician and scientist who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism".

Educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for t ...

,

Herbert Baxter Adams

Herbert Baxter Adams (April 16, 1850 – July 30, 1901) was an American educator and historian who brought German rigor to the study of history in America; a founding member of the American History Association; and one of the earliest ed ...

, and

G. Stanley Hall

Granville Stanley Hall (February 1, 1846 – April 24, 1924) was a pioneering American psychologist and educator. His interests focused on human life span development and evolutionary theory. Hall was the first president of the American Psy ...

, Dewey received his Ph.D. from the School of Arts & Sciences at

Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hem ...

. In 1884, he accepted a faculty position at the

University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

(1884–88 and 1889–94) with the help of George Sylvester Morris. His unpublished and now lost dissertation was titled "The Psychology of

Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aest ...

".

[''The New York Times''edition of January 19, 1953, page 27]

In 1894 Dewey joined the newly founded

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

(1894–1904) where he developed his belief in Rational

Empiricism, becoming associated with the newly emerging Pragmatic philosophy. His time at the University of Chicago resulted in four essays collectively entitled ''Thought and its Subject-Matter'', which was published with collected works from his colleagues at Chicago under the collective title ''Studies in Logical Theory'' (1904).

During that time Dewey also initiated the

University of Chicago Laboratory Schools

The University of Chicago Laboratory Schools (also known as Lab or Lab Schools and abbreviated as UCLS though the high school is nicknamed U-High) is a private, co-educational day Pre-K and K-12 school in Chicago, Illinois. It is affiliated with ...

, where he was able to actualize the pedagogical beliefs that provided material for his first major work on education, ''

The School and Society

''The School and Society: Being Three Lectures'' (1899) was John Dewey's first published work of length on education. A highly influential publication in its own right, it would also lay the foundation for his later work. In the lectures included i ...

'' (1899). Disagreements with the administration ultimately caused his resignation from the university, and soon thereafter he relocated near the East Coast. In 1899, Dewey was elected president of the

American Psychological Association

The American Psychological Association (APA) is the largest scientific and professional organization of psychologists in the United States, with over 133,000 members, including scientists, educators, clinicians, consultants, and students. It ha ...

(A.P.A.). From 1904 until his retirement in 1930 he was professor of philosophy at Teachers College at Columbia University and influenced

Carl Rogers

Carl Ransom Rogers (January 8, 1902 – February 4, 1987) was an American psychologist and among the founders of the humanistic approach (and client-centered approach) in psychology. Rogers is widely considered one of the founding fathers of ps ...

.

In 1905 he became president of the

American Philosophical Association

The American Philosophical Association (APA) is the main professional organization for philosophers in the United States. Founded in 1900, its mission is to promote the exchange of ideas among philosophers, to encourage creative and scholarl ...

. He was a longtime member of the

American Federation of Teachers

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) is the second largest teacher's labor union in America (the largest being the National Education Association). The union was founded in Chicago. John Dewey and Margaret Haley were founders.

About 60 per ...

. Along with the historians

Charles A. Beard and

James Harvey Robinson

James Harvey Robinson (June 29, 1863 – February 16, 1936) was an American scholar of history who, with Charles Austin Beard, founded New History, a disciplinary approach that attempts to use history to understand contemporary problems, which g ...

, and the economist

Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Bunde Veblen (July 30, 1857 – August 3, 1929) was a Norwegian-American economist and sociologist who, during his lifetime, emerged as a well-known critic of capitalism.

In his best-known book, ''The Theory of the Leisure Class'' ...

, Dewey is one of the founders of

The New School

The New School is a private research university in New York City. It was founded in 1919 as The New School for Social Research with an original mission dedicated to academic freedom and intellectual inquiry and a home for progressive thinkers. ...

.

Dewey published more than 700 articles in 140 journals, and approximately 40 books. His most significant writings were "The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology" (1896), a critique of a standard psychological concept and the basis of all his further work; ''

Democracy and Education

''Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education'' is a 1916 book by John Dewey.

Synopsis

In ''Democracy and Education'', Dewey argues that the primary ineluctable facts of the birth and death of each one of the constitu ...

'' (1916), his celebrated work on progressive education; ''Human Nature and Conduct'' (1922), a study of the function of habit in human behavior; ''

The Public and its Problems'' (1927), a defense of democracy written in response to

Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the te ...

's ''

The Phantom Public

''The Phantom Public'' is a book published in 1925 by journalist Walter Lippmann in which he expresses his Criticism of democracy, lack of faith in the democratic system by arguing that the public exists merely as an illusion, myth, and inevitabl ...

'' (1925); ''Experience and Nature'' (1925), Dewey's most "metaphysical" statement; ''Impressions of Soviet Russia and the Revolutionary World'' (1929), a glowing travelogue from the nascent

USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

''

Art as Experience

''Art as Experience'' (1934) is John Dewey's major writing on aesthetics, originally delivered as the first William James Lecture at Harvard (1932). Dewey's aesthetics have been found useful in a number of disciplines, including new media.

Dewe ...

'' (1934), was Dewey's major work on aesthetics; ''

A Common Faith'' (1934), a humanistic study of religion originally delivered as the

Dwight H. Terry Lectureship The Dwight H. Terry Lectureship, also known as the Terry Lectures, was established at Yale University in 1905 by a gift from Dwight H. Terry of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Its purpose is to engage both scholars and the public in a consideration of reli ...

at Yale; ''Logic: The Theory of Inquiry'' (1938), a statement of Dewey's unusual conception of logic; ''

Freedom and Culture

''Freedom and Culture'' is a book by John Dewey. Published in 1939, the book is an analytical defense of democracy written in a time when democratic regimes had recently been replaced by non-democratic ones, and at a time when Marxism was consider ...

'' (1939), a political work examining the roots of fascism; and ''

Knowing and the Known

''Knowing and the Known'' is a 1949 book by John Dewey and Arthur Bentley.

Overview

As well as a Preface, an Introduction and an Index, the book consists of 12 chapters, or papers, as the authors call them in their introduction. Chapters 1 (Vag ...

'' (1949), a book written in conjunction with

Arthur F. Bentley that systematically outlines the concept of trans-action, which is central to his other works (see

Transactionalism

Transactionalism is a pragmatic philosophical approach to how we are known, maintain health and relationships, and satisfy our goals for money and career through ambitious ecologies. It involves the study and accurate thinking required to plan a ...

).

While each of these works focuses on one particular philosophical theme, Dewey included his major themes in ''Experience and Nature''. However, dissatisfied with the response to the first (1925) edition, for the second (1929) edition he rewrote the first chapter and added a Preface in which he stated that the book presented what we would now call a new (Kuhnian) paradigm: ''

'I have not striven in this volume for a reconciliation between the new and the old'

&N:4' ''.'' and he asserts Kuhnian incommensurability:

''

'To many the associating of the two words

experience' and 'nature'will seem like talking of a round square' but 'I know of no route by which dialectical argument can answer such objections. They arise from association with words and cannot be dealt with argumentatively'.'' The following can be interpreted now as describing a Kuhnian conversion process: ''

'One can only hope in the course of the whole discussion to disclose the

ewmeanings which are attached to "experience" and "nature," and thus insensibly produce, if one is fortunate, a change in the significations previously attached to them'

ll E&N:10''

Reflecting his immense influence on 20th-century thought,

Hilda Neatby

Hilda Marion Ada Neatby (February 19, 1904May 14, 1975) was a Canadian historian and educator.

Early life and education

Hilda Marion Ada Neatby was born on February 19, 1904, in Sutton (then in Surrey), to Andrew Neatby and Ada Fisher. Th ...

wrote "Dewey has been to our age what

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

was to the

later Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

, not a philosopher, but ''the'' philosopher."

The

United States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal service in the U ...

honored Dewey with a

Prominent Americans series 30¢

postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the f ...

in 1968.

Personal life

Dewey married Alice Chipman in 1886 shortly after Chipman graduated with her Ph.D. from the University of Michigan. The two had six children: Frederick Archibald Dewey,

Evelyn Riggs Dewey, Morris (who died young), Gordon Chipman Dewey, Lucy Alice Chipman Dewey, and

Jane Mary Dewey. Alice Chipman died in 1927 at the age of 68; weakened by a case of malaria contracted during a trip to Turkey in 1924 and a heart attack during a trip to Mexico City in 1926, she died from cerebral thrombosis on July 13, 1927.

Dewey married Estelle Roberta Lowitz Grant, "a longtime friend and companion for several years before their marriage" on December 11, 1946. At Roberta's behest, the couple adopted two siblings, Lewis (changed to John, Jr.) and Shirley.

Death

John Dewey died of pneumonia on June 1, 1952, at his home in New York City after years of ill-health and was cremated the next day.

Visits to China and Japan

In 1919, Dewey and his wife traveled to Japan on

sabbatical leave

A sabbatical (from the Hebrew: (i.e., Sabbath); in Latin ; Greek: ) is a rest or break from work.

The concept of the sabbatical is based on the Biblical practice of '' shmita'' (sabbatical year), which is related to agriculture. According t ...

. Though Dewey and his wife were well received by the people of Japan during this trip, Dewey was also critical of the nation's governing system and claimed that the nation's path towards democracy was "ambitious but weak in many respects in which her competitors are strong".

[ The Trans-Pacific Experience of John Dewey]

/ref> He also warned that "the real test has not yet come. But if the nominally democratic world should go back on the professions so profusely uttered during war days, the shock will be enormous, and bureaucracy and militarism might come back."Hu Shih

Hu Shih (; 17 December 1891 – 24 February 1962), also known as Hu Suh in early references, was a Chinese diplomat, essayist, literary scholar, philosopher, and politician. Hu is widely recognized today as a key contributor to Chinese libera ...

and Chiang Monlin

Jiang Menglin (; 20 January 1886 – 1964), also known as Chiang Monlin, was a Chinese educator, writer, and politician. Between 1919 and 1927, he also served as the President of Peking University. He later became the president of National Che ...

. Dewey and his wife Alice arrived in Shanghai on April 30, 1919, just days before student demonstrators took to the streets of Peking to protest the decision of the Allies in Paris to cede the German-held territories in Shandong province to Japan. Their demonstrations on May Fourth excited and energized Dewey, and he ended up staying in China for two years, leaving in July 1921.

In these two years, Dewey gave nearly 200 lectures to Chinese audiences and wrote nearly monthly articles for Americans in ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hum ...

'' and other magazines. Well aware of both Japanese expansionism into China and the attraction of Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, ...

to some Chinese, Dewey advocated that Americans support China's transformation and that Chinese base this transformation in education and social reforms, not revolution. Hundreds and sometimes thousands of people attended the lectures, which were interpreted by Hu Shih. For these audiences, Dewey represented "Mr. Democracy" and "Mr. Science," the two personifications which they thought of representing modern values and hailed him as "Second Confucius". His lectures were lost at the time, but have been rediscovered and published in 2015.

Zhixin Su states:

:Dewey was, for those Chinese educators who had studied under him, the great apostle of philosophic liberalism and experimental methodology, the advocate of complete freedom of thought, and the man who, above all other teachers, equated education to the practical problems of civic cooperation and useful living.

Dewey urged the Chinese to not import any Western educational model. He recommended to educators such as Tao Xingzhi

Tao Xingzhi (; October 18, 1891 – July 25, 1946), was a renowned Chinese educator and reformer in the Republic of China mainland era. He studied at Teachers College, Columbia University and returned to China to champion progressive education. ...

, that they use pragmatism to devise their own model school system at the national level. However the national government was weak, and the provinces largely controlled by warlords so his suggestions were praised at the national level but not implemented. However, there were a few implementations locally. Dewey's ideas did have influence in Hong Kong, and in Taiwan after the nationalist government fled there. In most of China, Confucian scholars controlled the local educational system before 1949 and they simply ignored Dewey and Western ideas. In Marxist and Maoist China, Dewey's ideas were systematically denounced.

Visit to Southern Africa

Dewey and his daughter Jane went to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

in July 1934, at the invitation of the World Conference of New Education Fellowship in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

and Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Dem ...

, where he delivered several talks. The conference was opened by the South African Minister of Education Jan Hofmeyr, and Deputy Prime Minister Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

. Other speakers at the conference included Max Eiselen

Werner Willi Max Eiselen (1899–1977) was a South African anthropologist and linguist. He was an ally and associate of Hendrik Verwoerd, the Minister of Bantu Administration and Development, and Bantu Education, Minister of Native Affairs f ...

and Hendrik Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966) was a South African politician, a scholar of applied psychology and sociology, and chief editor of '' Die Transvaler'' newspaper. He is commonly regarded as the architect ...

, who would later become prime minister of the Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

government that introduced apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

.

Dewey's expenses were paid by the Carnegie Foundation. He also traveled to Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

, Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends eastward into the foot ...

and Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls ( Lozi: ''Mosi-oa-Tunya'', "The Smoke That Thunders"; Tonga: ''Shungu Namutitima'', "Boiling Water") is a waterfall on the Zambezi River in southern Africa, which provides habitat for several unique species of plants and anim ...

in what was then Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kno ...

(now Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and ...

) and looked at schools, talked to pupils, and gave lectures to the administrators and teachers. In August 1934, Dewey accepted an honorary degree from the University of the Witwatersrand

The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (), is a multi-campus South African public research university situated in the northern areas of central Johannesburg. It is more commonly known as Wits University or Wits ( or ). The university ...

. The white-only governments rejected Dewey's ideas as too secular. However black people and their white supporters were more receptive.

Functional psychology

At the University of Michigan, Dewey published his first two books, ''Psychology'' (1887), and ''Leibniz's New Essays Concerning the Human Understanding'' (1888), both of which expressed Dewey's early commitment to British neo-Hegelianism. In ''Psychology'', Dewey attempted a synthesis between idealism and experimental science.James Hayden Tufts

James Hayden Tufts (1862–1942), an influential American philosopher, was a professor of the then newly founded Chicago University. Tufts was also a member of the Board of Arbitration, and the chairman of a committee of the social agencies ...

and George Herbert Mead

George Herbert Mead (February 27, 1863 – April 26, 1931) was an American philosopher, sociologist, and psychologist, primarily affiliated with the University of Chicago, where he was one of several distinguished pragmatists. He is regarded a ...

, together with his student James Rowland Angell

James Rowland Angell (; May 8, 1869 – March 4, 1949) was an American psychologist and educator who served as the 16th President of Yale University between 1921 and 1937. His father, James Burrill Angell (1829–1916), was president of the Un ...

, all influenced strongly by the recent publication of William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

' '' Principles of Psychology'' (1890), began to reformulate psychology, emphasizing the social environment on the activity of mind and behavior rather than the physiological psychology of Wilhelm Wundt and his followers.

By 1894, Dewey had joined Tufts, with whom he would later write ''Ethics'' (1908) at the recently founded University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

and invited Mead and Angell to follow him, the four men forming the basis of the so-called "Chicago group" of psychology.

Their new style of psychology, later dubbed functional psychology

Functional psychology or functionalism refers to a psychological school of thought that was a direct outgrowth of Darwinian thinking which focuses attention on the utility and purpose of behavior that has been modified over years of human existen ...

, had a practical emphasis on action and application. In Dewey's article "The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology" which appeared in ''Psychological Review

''Psychological Review'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed academic journal that covers psychological theory. It was established by James Mark Baldwin (Princeton University) and James McKeen Cattell (Columbia University) in 1894 as a publication vehi ...

'' in 1896, he reasons against the traditional stimulus-response understanding of the reflex arc

A reflex arc is a neural pathway that controls a reflex. In vertebrates, most sensory neurons do not pass directly into the brain, but synapse in the spinal cord. This allows for faster reflex actions to occur by activating spinal motor neurons w ...

in favor of a "circular" account in which what serves as "stimulus" and what as "response" depends on how one considers the situation, and defends the unitary nature of the sensory motor circuit. While he does not deny the existence of stimulus, sensation, and response, he disagreed that they were separate, juxtaposed events happening like links in a chain. He developed the idea that there is a coordination by which the stimulation is enriched by the results of previous experiences. The response is modulated by sensorial experience.

Dewey was elected president of the American Psychological Association in 1899.

Dewey also expressed interest in work in the psychology of visual perception

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding Biophysical environment, environment through photopic vision (daytime vision), color vision, scotopic vision (night vision), and mesopic vision (twilight vision), using light in the ...

performed by Dartmouth research professor Adelbert Ames Jr.

Adelbert Ames Jr. (August 19, 1880 – July 3, 1955) was an American scientist who made contributions to physics, physiology, ophthalmology, psychology, and philosophy. He pioneered the study of physiological optics at Dartmouth College, serving ...

He had great trouble with listening, however, because it is known Dewey could not distinguish musical pitches—in other words was an amusic.

Pragmatism, instrumentalism, consequentialism

Dewey sometimes referred to his philosophy as

Dewey sometimes referred to his philosophy as instrumentalism

In philosophy of science and in epistemology, instrumentalism is a methodological view that ideas are useful instruments, and that the worth of an idea is based on how effective it is in explaining and predicting phenomena.

According to instrumenta ...

rather than pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that considers words and thought as tools and instruments for prediction, problem solving, and action, and rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. ...

, and would have recognized the similarity of these two schools to the newer school named consequentialism

In ethical philosophy, consequentialism is a class of normative, teleological ethical theories that holds that the consequences of one's conduct are the ultimate basis for judgment about the rightness or wrongness of that conduct. Thus, fro ...

. In some phrases introducing a book he wrote later in life meant to help forestay a wandering kind of criticism of the work based on the controversies due to the differences in the schools that he sometimes invoked, he defined at the same time with precise brevity the criterion of validity common to these three schools, which lack agreed-upon definitions:

His concern for precise definition led him to detailed analysis of careless word usage, reported in ''Knowing and the Known'' in 1949.

Epistemology

The terminology problem in the fields of epistemology and logic is partially due, according to Dewey and Bentley, to inefficient and imprecise use of words and concepts that reflect three historic levels of organization and presentation. In the order of chronological appearance, these are:

* Self-Action: Prescientific concepts regarded humans, animals, and things as possessing powers of their own which initiated or caused their actions.

* Interaction: as described by Newton, where things, living and inorganic, are balanced against something in a system of interaction, for example, the third law of motion states that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

* Transaction: where modern systems of descriptions and naming are employed to deal with multiple aspects and phases of action without any attribution to ultimate, final, or independent entities, essences, or realities.

A series of characterizations of Transactions indicate the wide range of considerations involved.

Logic and method

Dewey sees paradox in contemporary logical theory. Proximate subject matter garners general agreement and advancement, while the ultimate subject matter of logic generates unremitting controversy. In other words, he challenges confident logicians to answer the question of the truth of logical operators. Do they function merely as abstractions (e.g., pure mathematics) or do they connect in some essential way with their objects, and therefore alter or bring them to light?

Dewey sees paradox in contemporary logical theory. Proximate subject matter garners general agreement and advancement, while the ultimate subject matter of logic generates unremitting controversy. In other words, he challenges confident logicians to answer the question of the truth of logical operators. Do they function merely as abstractions (e.g., pure mathematics) or do they connect in some essential way with their objects, and therefore alter or bring them to light?Louis Menand

Louis Menand (; born January 21, 1952) is an American critic, essayist, and professor, best known for his Pulitzer-winning book '' The Metaphysical Club'' (2001), an intellectual and cultural history of late 19th and early 20th century America.

...

argues in ''The Metaphysical Club

The Metaphysical Club was a name attributed by the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, in an unpublished paper over thirty years after its foundation, to a conversational philosophical club that Peirce, the future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wend ...

'' that Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

had been critical of Dewey's emphasis on antagonism in the context of a discussion of the Pullman strike

The Pullman Strike was two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman factory in Chi ...

of 1894. In a later letter to his wife, Dewey confessed that Addams' argument was:

He went on to add:

In a letter to Addams, clearly influenced by his conversation with her, Dewey wrote:

Aesthetics

''Art as Experience'' (1934) is Dewey's major writing on aesthetics.

It is, in accordance with his place in the Pragmatist tradition that emphasizes community, a study of the individual art object as embedded in (and inextricable from) the experiences of a local culture. In the original illustrated edition, Dewey drew on the modern art and world cultures collection assembled by Albert C. Barnes at the Barnes Foundation

The Barnes Foundation is an art collection and educational institution promoting the appreciation of art and horticulture. Originally in Merion, the art collection moved in 2012 to a new building on Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, Penn ...

, whose own ideas on the application of art to one's way of life was influenced by Dewey's writing. Dewey made art through writing poetry, but he considered himself deeply unmusical: one of his students described Dewey as "allergic to music." Barnes was particularly influenced by ''Democracy and Education'' (1916) and then attended Dewey's seminar on political philosophy at Columbia University in the fall semester of 1918.

On philanthropy, women and democracy

Dewey founded the University of Chicago laboratory school

A laboratory school or demonstration school is an elementary or secondary school operated in association with a university, college, or other teacher education institution and used for the training of future teachers, educational experimentation, ...

, supported educational organizations, and supported settlement houses especially Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

' Hull House.Hull House

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of the city, Hull House (named after the original house's first owner Cha ...

serving on its first board of trustees, Dewey was not only an activist for the cause but also a partner working to serve the large immigrant community of Chicago and women's suffrage. Dewey experienced the lack of children's education while contributing in the classroom at the Hull House. There he also experienced the lack of education and skills of immigrant women.

First, Dewey believed that democracy is an ethical ideal rather than merely a political arrangement. Second, he considered participation, not representation, the essence of democracy. Third, he insisted on the harmony between democracy and the scientific method: ever-expanding and self-critical communities of inquiry, operating on pragmatic principles and constantly revising their beliefs in light of new evidence, provided Dewey with a model for democratic decision making ... Finally, Dewey called for extending democracy, conceived as an ethical project, from politics to industry and society.

This helped to shape his understanding of human action and the unity of human experience.

Dewey believed that a woman's place in society was determined by her environment and not just her biology. On women he says, "You think too much of women in terms of sex. Think of them as human individuals for a while, dropping out the sex qualification, and you won't be so sure of some of your generalizations about what they should and shouldn't do".B.R. Ambedkar

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (14 April 1891 – 6 December 1956) was an Indian jurist, economist, social reformer and political leader who headed the committee drafting the Constitution of India from the Constituent Assembly debates, served ...

, one of his students, who later served as a Law and Justice Minister of India.

On education and teacher education

Dewey's educational theories were presented in ''My Pedagogic Creed

"My Pedagogic Creed" is an article written by John Dewey and published in ''School Journal'' in 1897.Dewey, John (1897). My Pedagogic Creed. ''School Journal'', 54(3), 77–80. The article is broken into 5 sections, with each paragraph beginning " ...

'' (1897), ''The Primary-Education Fetich'' (1898), ''The School and Society

''The School and Society: Being Three Lectures'' (1899) was John Dewey's first published work of length on education. A highly influential publication in its own right, it would also lay the foundation for his later work. In the lectures included i ...

'' (1900), ''The Child and the Curriculum'' (1902), ''Democracy and Education

''Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education'' is a 1916 book by John Dewey.

Synopsis

In ''Democracy and Education'', Dewey argues that the primary ineluctable facts of the birth and death of each one of the constitu ...

'' (1916)

''Schools of To-morrow''

(1915) with Evelyn Dewey, and '' Experience and Education'' (1938). Several themes recur throughout these writings. Dewey continually argues that education and learning are social and interactive processes, and thus the school itself is a social institution through which social reform can and should take place. In addition, he believed that students thrive in an environment where they are allowed to experience and interact with the curriculum, and all students should have the opportunity to take part in their own learning.

The ideas of democracy and social reform are continually discussed in Dewey's writings on education. Dewey makes a strong case for the importance of education not only as a place to gain content knowledge, but also as a place to learn how to live. In his eyes, the purpose of education should not revolve around the acquisition of a pre-determined set of skills, but rather the realization of one's full potential and the ability to use those skills for the greater good. He notes that "to prepare him for the future life means to give him command of himself; it means so to train him that he will have the full and ready use of all his capacities" (''My Pedagogic Creed'', Dewey, 1897).

In addition to helping students realize their full potential, Dewey goes on to acknowledge that education and schooling are instrumental in creating social change and reform. He notes that "education is a regulation of the process of coming to share in the social consciousness; and that the adjustment of individual activity on the basis of this social consciousness is the only sure method of social reconstruction".

In addition to his ideas regarding what education is and what effect it should have on society, Dewey also had specific notions regarding how education should take place within the classroom. In ''The Child and the Curriculum'' (1902), Dewey discusses two major conflicting schools of thought regarding educational pedagogy. The first is centered on the curriculum and focuses almost solely on the subject matter to be taught. Dewey argues that the major flaw in this methodology is the inactivity of the student; within this particular framework, "the child is simply the immature being who is to be matured; he is the superficial being who is to be deepened" (1902, p. 13). He argues that in order for education to be most effective, content must be presented in a way that allows the student to relate the information to prior experiences, thus deepening the connection with this new knowledge.

At the same time, Dewey was alarmed by many of the "child-centered" excesses of educational-school pedagogues who claimed to be his followers, and he argued that too much reliance on the child could be equally detrimental to the learning process. In this second school of thought, "we must take our stand with the child and our departure from him. It is he and not the subject-matter which determines both quality and quantity of learning" (Dewey, 1902, pp. 13–14). According to Dewey, the potential flaw in this line of thinking is that it minimizes the importance of the content as well as the role of the teacher.

In order to rectify this dilemma, Dewey advocated an educational structure that strikes a balance between delivering knowledge while also taking into account the interests and experiences of the student. He notes that "the child and the curriculum are simply two limits which define a single process. Just as two points define a straight line, so the present standpoint of the child and the facts and truths of studies define instruction" (Dewey, 1902, p. 16).

It is through this reasoning that Dewey became one of the most famous proponents of hands-on learning

Experiential learning (ExL) is the process of learning through experience, and is more narrowly defined as "learning through reflection on doing". Hands-on learning can be a form of experiential learning, but does not necessarily involve students ...

or experiential education

Experiential education is a philosophy of education that describes the process that occurs between a teacher and student that infuses direct experience with the learning environment and content. The term is not interchangeable with experientia ...

, which is related to, but not synonymous with experiential learning

Experiential learning (ExL) is the process of learning through experience, and is more narrowly defined as "learning through reflection on doing". Hands-on learning can be a form of experiential learning, but does not necessarily involve students ...

. He argued that "if knowledge comes from the impressions made upon us by natural objects, it is impossible to procure knowledge without the use of objects which impress the mind" (Dewey, 1916/2009, pp. 217–18). Dewey's ideas went on to influence many other influential experiential models and advocates. Problem-Based Learning

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered pedagogy in which students learn about a subject through the experience of solving an open-ended problem found in trigger material. The PBL process does not focus on problem solving with a defi ...

(PBL), for example, a method used widely in education today, incorporates Dewey's ideas pertaining to learning through active inquiry.

Dewey not only re-imagined the way that the learning process should take place, but also the role that the teacher should play within that process. Throughout the history of American schooling, education's purpose has been to train students for work by providing the student with a limited set of skills and information to do a particular job. The works of John Dewey provide the most prolific examples of how this limited vocational view of education has been applied to both the K–12 public education system and to the teacher training schools that attempted to quickly produce proficient and practical teachers with a limited set of instructional and discipline-specific skills needed to meet the needs of the employer and demands of the workforce.

In ''The School and Society'' (Dewey, 1899) and ''Democracy of Education'' (Dewey, 1916), Dewey claims that rather than preparing citizens for ethical participation in society, schools cultivate passive pupils via insistence upon mastery of facts and disciplining of bodies. Rather than preparing students to be reflective, autonomous and ethical beings capable of arriving at social truths through critical and intersubjective discourse, schools prepare students for docile compliance with authoritarian work and political structures, discourage the pursuit of individual and communal inquiry, and perceive higher learning as a monopoly of the institution of education (Dewey, 1899; 1916).

For Dewey and his philosophical followers, education stifles individual autonomy when learners are taught that knowledge is transmitted in one direction, from the expert to the learner. Dewey not only re-imagined the way that the learning process should take place, but also the role that the teacher should play within that process. For Dewey, "The thing needful is improvement of education, not simply by turning out teachers who can do better the things that are not necessary to do, but rather by changing the conception of what constitutes education" (Dewey, 1904, p. 18).

Dewey's qualifications for teaching—a natural love for working with young children, a natural propensity to inquire about the subjects, methods and other social issues related to the profession, and a desire to share this acquired knowledge with others—are not a set of outwardly displayed mechanical skills. Rather, they may be viewed as internalized principles or habits which "work automatically, unconsciously" (Dewey, 1904, p. 15). Turning to Dewey's essays and public addresses regarding the teaching profession, followed by his analysis of the teacher as a person and a professional, as well as his beliefs regarding the responsibilities of teacher education programs to cultivate the attributes addressed, teacher educators can begin to reimagine the successful classroom teacher Dewey envisioned.

Professionalization of teaching as a social service

For many, education's purpose is to train students for work by providing the student with a limited set of skills and information to do a particular job. As Dewey notes, this limited vocational view is also applied to teacher training schools who attempt to quickly produce proficient and practical teachers with a limited set of instructional and discipline skills needed to meet the needs of the employer and demands of the workforce (Dewey, 1904). For Dewey, the school and the classroom teacher, as a workforce and provider of social service, have a unique responsibility to produce psychological and social goods that will lead to both present and future social progress.

As Dewey notes, "The business of the teacher is to produce a higher standard of intelligence in the community, and the object of the public school system is to make as large as possible the number of those who possess this intelligence. Skill, the ability to act wisely and effectively in a great variety of occupations and situations, is a sign and a criterion of the degree of civilization that a society has reached. It is the business of teachers to help in producing the many kinds of skills needed in contemporary life. If teachers are up to their work, they also aid in the production of character."(Dewey, TAP, 2010, pp. 241–42).

According to Dewey, the emphasis is placed on producing these attributes in children for use in their contemporary life because it is "impossible to foretell definitely just what civilization will be twenty years from now" (Dewey, MPC, 2010, p. 25). However, although Dewey is steadfast in his beliefs that education serves an immediate purpose (Dewey, DRT, 2010; Dewey, MPC, 2010; Dewey, TTP, 2010), he is not ignorant of the impact imparting these qualities of intelligence, skill, and character on young children in their present life will have on the future society. While addressing the state of educative and economic affairs during a 1935 radio broadcast, Dewey linked the ensuing economic depression to a "lack of sufficient production of intelligence, skill, and character" (Dewey, TAP, 2010, p. 242) of the nation's workforce.

As Dewey notes, there is a lack of these goods in the present society and teachers have a responsibility to create them in their students, who, we can assume, will grow into the adults who will ultimately go on to participate in whatever industrial or economic civilization awaits them. According to Dewey, the profession of the classroom teacher is to produce the intelligence, skill, and character within each student so that the democratic community is composed of citizens who can think, do and act intelligently and morally.

A teacher's knowledge

Dewey believed that successful classroom teacher possesses a passion for knowledge and intellectual curiosity in the materials and methods they teach. For Dewey, this propensity is an inherent curiosity and love for learning that differs from one's ability to acquire, recite and reproduce textbook knowledge. "No one," according to Dewey, "can be really successful in performing the duties and meeting these demands f teachingwho does not retain erintellectual curiosity intact throughout erentire career" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 34).

According to Dewey, it is not that the "teacher ought to strive to be a high-class scholar in all the subjects he or she has to teach," rather, "a teacher ought to have an unusual love and aptitude in some one subject: history, mathematics, literature, science, a fine art, or whatever" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 35). The classroom teacher does not have to be a scholar in all subjects; rather, genuine love in one will elicit a feel for genuine information and insight in all subjects taught.

In addition to this propensity for study into the subjects taught, the classroom teacher "is possessed by a recognition of the responsibility for the constant study of school room work, the constant study of children, of methods, of subject matter in its various adaptations to pupils" (Dewey, PST, 2010, p. 37). For Dewey, this desire for the lifelong pursuit of learning is inherent in other professions (e.g. the architectural, legal and medical fields; Dewey, 1904 & Dewey, PST, 2010), and has particular importance for the field of teaching. As Dewey notes, "this further study is not a sideline but something which fits directly into the demands and opportunities of the vocation" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 34).

According to Dewey, this propensity and passion for intellectual growth in the profession must be accompanied by a natural desire to communicate one's knowledge with others. "There are scholars who have he knowledge

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

in a marked degree but who lack enthusiasm for imparting it. To the 'natural born' teacher learning is incomplete unless it is shared" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 35). For Dewey, it is not enough for the classroom teacher to be a lifelong learner of the techniques and subject-matter of education; she must aspire to share what she knows with others in her learning community.

A teacher's skill

The best indicator of teacher quality, according to Dewey, is the ability to watch and respond to the movement of the mind with keen awareness of the signs and quality of the responses he or her students exhibit with regard to the subject-matter presented (Dewey, APT, 2010; Dewey, 1904). As Dewey notes, "I have often been asked how it was that some teachers who have never studied the art of teaching are still extraordinarily good teachers. The explanation is simple. They have a quick, sure and unflagging sympathy with the operations and process of the minds they are in contact with. Their own minds move in harmony with those of others, appreciating their difficulties, entering into their problems, sharing their intellectual victories" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 36).

Such a teacher is genuinely aware of the complexities of this mind to mind transfer, and she has the intellectual fortitude to identify the successes and failures of this process, as well as how to appropriately reproduce or correct it in the future.

A teacher's disposition

As a result of the direct influence teachers have in shaping the mental, moral and spiritual lives of children during their most formative years, Dewey holds the profession of teaching in high esteem, often equating its social value to that of the ministry and to parenting (Dewey, APT, 2010; Dewey, DRT, 2010; Dewey, MPC, 2010; Dewey, PST, 2010; Dewey, TTC, 2010; Dewey, TTP, 2010). Perhaps the most important attributes, according to Dewey, are those personal inherent qualities that the teacher brings to the classroom. As Dewey notes, "no amount of learning or even of acquired pedagogical skill makes up for the deficiency" (Dewey, TLS, p. 25) of the personal traits needed to be most successful in the profession.

According to Dewey, the successful classroom teacher occupies an indispensable passion for promoting the intellectual growth of young children. In addition, they know that their career, in comparison to other professions, entails stressful situations, long hours, and limited financial reward; all of which have the potential to overcome their genuine love and sympathy for their students.

For Dewey, "One of the most depressing phases of the vocation is the number of careworn teachers one sees, with anxiety depicted on the lines of their faces, reflected in their strained high pitched voices and sharp manners. While contact with the young is a privilege for some temperaments, it is a tax on others and a tax which they do not bear up under very well. And in some schools, there are too many pupils to a teacher, too many subjects to teach, and adjustments to pupils are made in a mechanical rather than a human way. Human nature reacts against such unnatural conditions" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 35).

It is essential, according to Dewey, that the classroom teacher has the mental propensity to overcome the demands and stressors placed on them because the students can sense when their teacher is not genuinely invested in promoting their learning (Dewey, PST, 2010). Such negative demeanors, according to Dewey, prevent children from pursuing their own propensities for learning and intellectual growth. It can therefore be assumed that if teachers want their students to engage with the educational process and employ their natural curiosities for knowledge, teachers must be aware of how their reactions to young children and the stresses of teaching influence this process.

The role of teacher education to cultivate the professional classroom teacher

Dewey's passions for teaching—a natural love for working with young children, a natural propensity to inquire about the subjects, methods and other social issues related to the profession, and a desire to share this acquired knowledge with others—are not a set of outwardly displayed mechanical skills. Rather, they may be viewed as internalized principles or habits which "work automatically, unconsciously" (Dewey, 1904, p. 15). According to Dewey, teacher-education programs must turn away from focusing on producing proficient practitioners because such practical skills related to instruction and discipline (e.g. creating and delivering lesson plans, classroom management, implementation of an assortment of content-specific methods) can be learned over time during their everyday school work with their students (Dewey, PST, 2010).

As Dewey notes, "The teacher who leaves the professional school with power in managing a class of children may appear to superior advantage the first day, the first week, the first month, or even the first year, as compared with some other teacher who has a much more vital command of the psychology, logic and ethics of development. But later 'progress' may consist only in perfecting and refining skill already possessed. Such persons seem to know how to teach, but they are not students of teaching. Even though they go on studying books of pedagogy, reading teachers' journals, attending teachers' institutes, etc., yet the root of the matter is not in them, unless they continue to be students of subject-matter, and students of mind-activity. Unless a teacher is such a student, he may continue to improve in the mechanics of school management, but he cannot grow as a teacher, an inspirer and director of soul-life" (Dewey, 1904, p. 15).

For Dewey, teacher education should focus not on producing persons who know how to teach as soon as they leave the program; rather, teacher education should be concerned with producing professional students of education who have the propensity to inquire about the subjects they teach, the methods used, and the activity of the mind as it gives and receives knowledge. According to Dewey, such a student is not superficially engaging with these materials, rather, the professional student of education has a genuine passion to inquire about the subjects of education, knowing that doing so ultimately leads to acquisitions of the skills related to teaching. Such students of education aspire for the intellectual growth within the profession that can only be achieved by immersing one's self in the lifelong pursuit of the intelligence, skills and character Dewey linked to the profession.

As Dewey notes, other professional fields, such as law and medicine cultivate a professional spirit in their fields to constantly study their work, their methods of their work, and a perpetual need for intellectual growth and concern for issues related to their profession. Teacher education, as a profession, has these same obligations (Dewey, 1904; Dewey, PST, 2010).

As Dewey notes, "An intellectual responsibility has got to be distributed to every human being who is concerned in carrying out the work in question, and to attempt to concentrate intellectual responsibility for a work that has to be done, with their brains and their hearts, by hundreds or thousands of people in a dozen or so at the top, no matter how wise and skillful they are, is not to concentrate responsibility—it is to diffuse irresponsibility" (Dewey, PST, 2010, p. 39). For Dewey, the professional spirit of teacher education requires of its students a constant study of school room work, constant study of children, of methods, of subject matter in its various adaptations to pupils. Such study will lead to professional enlightenment with regard to the daily operations of classroom teaching.

As well as his very active and direct involvement in setting up educational institutions such as the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools

The University of Chicago Laboratory Schools (also known as Lab or Lab Schools and abbreviated as UCLS though the high school is nicknamed U-High) is a private, co-educational day Pre-K and K-12 school in Chicago, Illinois. It is affiliated with ...

(1896) and The New School for Social Research

The New School for Social Research (NSSR) is a graduate-level educational institution that is one of the divisions of The New School in New York City, United States. The university was founded in 1919 as a home for progressive era thinkers. NSS ...

(1919), many of Dewey's ideas influenced the founding of Bennington College

Bennington College is a private liberal arts college in Bennington, Vermont. Founded in 1932 as a women's college, it became co-educational in 1969. It claims to be the first college to include visual and performing arts as an equal partner in ...

and Goddard College in Vermont, where he served on the board of trustees. Dewey's works and philosophy also held great influence in the creation of the short-lived Black Mountain College

Black Mountain College was a private liberal arts college in Black Mountain, North Carolina. It was founded in 1933 by John Andrew Rice, Theodore Dreier, and several others. The college was ideologically organized around John Dewey's educational ...

in North Carolina, an experimental college focused on interdisciplinary study, and whose faculty included Buckminster Fuller

Richard Buckminster Fuller (; July 12, 1895 – July 1, 1983) was an American architect, systems theorist, writer, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist. He styled his name as R. Buckminster Fuller in his writings, publishing mo ...

, Willem de Kooning

Willem de Kooning (; ; April 24, 1904 – March 19, 1997) was a Dutch-American abstract expressionist artist. He was born in Rotterdam and moved to the United States in 1926, becoming an American citizen in 1962. In 1943, he married painter El ...

, Charles Olson

Charles Olson (27 December 1910 – 10 January 1970) was a second generation modern American poet who was a link between earlier figures such as Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams and the New American poets, which includes the New York ...

, Franz Kline

Franz Kline (May 23, 1910 – May 13, 1962) was an American painter. He is associated with the Abstract Expressionist movement of the 1940s and 1950s. Kline, along with other action painters like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Mot ...

, Robert Duncan, Robert Creeley

Robert White Creeley (May 21, 1926 – March 30, 2005) was an American poet and author of more than sixty books. He is usually associated with the Black Mountain poets, though his verse aesthetic diverged from that school. He was close with Char ...

, and Paul Goodman

Paul Goodman (1911–1972) was an American writer and public intellectual best known for his 1960s works of social criticism. Goodman was prolific across numerous literary genres and non-fiction topics, including the arts, civil rights, decen ...

, among others. Black Mountain College was the locus of the "Black Mountain Poets" a group of avant-garde poets closely linked with the Beat Generation and the San Francisco Renaissance

The term San Francisco Renaissance is used as a global designation for a range of poetic activity centered on San Francisco, which brought it to prominence as a hub of the American poetry avant-garde in the 1950s. However, others (e.g., Alan Watt ...

.

On journalism

Since the mid-1980s, Dewey's ideas have experienced revival as a major source of inspiration for the public journalism movement. Dewey's definition of "public," as described in '' The Public and its Problems'', has profound implications for the significance of journalism in society. As suggested by the title of the book, his concern was of the transactional relationship between publics and problems. Also implicit in its name, public journalism seeks to orient communication away from elite, corporate hegemony toward a civic public sphere. "The 'public' of public journalists is Dewey's public."

Dewey gives a concrete definition to the formation of a public. Publics are spontaneous groups of citizens who share the indirect effects of a particular action. Anyone affected by the indirect consequences of a specific action will automatically share a common interest in controlling those consequences, i.e., solving a common problem.

Since the mid-1980s, Dewey's ideas have experienced revival as a major source of inspiration for the public journalism movement. Dewey's definition of "public," as described in '' The Public and its Problems'', has profound implications for the significance of journalism in society. As suggested by the title of the book, his concern was of the transactional relationship between publics and problems. Also implicit in its name, public journalism seeks to orient communication away from elite, corporate hegemony toward a civic public sphere. "The 'public' of public journalists is Dewey's public."

Dewey gives a concrete definition to the formation of a public. Publics are spontaneous groups of citizens who share the indirect effects of a particular action. Anyone affected by the indirect consequences of a specific action will automatically share a common interest in controlling those consequences, i.e., solving a common problem.

Since every action generates unintended consequence

In the social sciences, unintended consequences (sometimes unanticipated consequences or unforeseen consequences) are outcomes of a purposeful action that are not intended or foreseen. The term was popularised in the twentieth century by Ameri ...

s, publics continuously emerge, overlap, and disintegrate.

In ''The Public and its Problems'', Dewey presents a rebuttal to Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the te ...

's treatise on the role of journalism in democracy. Lippmann's model was a basic transmission model in which journalists took information given to them by experts and elites, repackaged that information in simple terms, and transmitted the information to the public, whose role was to react emotionally to the news. In his model, Lippmann supposed that the public was incapable of thought or action, and that all thought and action should be left to the experts and elites.

Dewey refutes this model by assuming that politics is the work and duty of each individual in the course of his daily routine. The knowledge needed to be involved in politics, in this model, was to be generated by the interaction of citizens, elites, experts, through the mediation and facilitation of journalism. In this model, not just the government is accountable, but the citizens, experts, and other actors as well.

Dewey also said that journalism should conform to this ideal by changing its emphasis from actions or happenings (choosing a winner of a given situation) to alternatives, choices, consequences, and conditions, in order to foster conversation and improve the generation of knowledge. Journalism would not just produce a static product that told what had already happened, but the news would be in a constant state of evolution as the public added value by generating knowledge. The "audience" would end, to be replaced by citizens and collaborators who would essentially be users, doing more with the news than simply reading it. Concerning his effort to change journalism, he wrote in ''The Public and Its Problems'': "Till the Great Society is converted in to a Great Community, the Public will remain in eclipse. Communication can alone create a great community" (Dewey, p. 142).

Dewey believed that communication creates a great community, and citizens who participate actively with public life contribute to that community. "The clear consciousness of a communal life, in all its implications, constitutes the idea of democracy." (''The Public and its Problems'', p. 149). This Great Community can only occur with "free and full intercommunication." (p. 211) Communication can be understood as journalism.

On humanism

As an atheist and a secular humanist

Secular humanism is a philosophy, belief system or life stance that embraces human reason, secular ethics, and philosophical naturalism while specifically rejecting religious dogma, supernaturalism, and superstition as the basis of morality ...

in his later life, Dewey participated with a variety of humanistic activities from the 1930s into the 1950s, which included sitting on the advisory board of Charles Francis Potter

Charles Francis Potter (October 28, 1885 – October 4, 1962) was an American Unitarian minister, theologian, and author.

In 1923 and 1924, he became nationally known through a series of debates with John Roach Straton, a fundamentalist Chri ...

's First Humanist Society of New York

In 1929 Charles Francis Potter founded the First Humanist Society of New York whose advisory board included Julian Huxley, John Dewey, Albert Einstein, and Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German n ...

(1929); being one of the original 34 signatories of the first ''Humanist Manifesto

''Humanist Manifesto'' is the title of three manifestos laying out a humanist worldview. They are the original '' Humanist Manifesto'' (1933, often referred to as Humanist Manifesto I), the ''Humanist Manifesto II'' (1973), and ''Humanism and I ...

'' (1933) and being elected an honorary member of the Humanist Press Association (1936).

His opinion of humanism is summarized in his own words from an article titled "What Humanism Means to Me", published in the June 1930 edition of ''Thinker 2'':

Social and political activism

1894 Pullman Strike

While Dewey was at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

, his letters to his wife Alice and his colleague Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

reveal that he closely followed the 1894 Pullman Strike

The Pullman Strike was two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman factory in Chi ...

, in which the employees of the Pullman Palace Car Factory in Chicago decided to go on strike after industrialist George Pullman